The Magnificent Offal: Шкембиђи у Сафту a.k.a. The Ancient Tripe

This is a precarious post - I mildly suspect it will cost me at least 80% of my readership - an observation based on the highly conservative estimate for the percentage of mankind whose stomachs turn at the bare mention of cow's stomach or any of the other semantically neighboring body parts from nose to tail classified as offal. If a blogger cares about the size of its audience and a broad reach to culinary masses, writing about offal is not the best of ideas. (Just as a side remark, it appears that in the world of food bloggers, the road to popularity, to countless hits and to massive following is often paved with posts about cookies, kale and adaptations of David Chang's recipes. Here we go, this remark will probably cost me another 50% of the remaining readership.)

As much as my blogger's ego tells me not to go down the slippery slope, I cannot help it; the urge to cook tripe, photograph tripe and most of all eat tripe is beyond my point of resistance and hence here it is, the post about cow's stomach. (By the way, I did my share of cakes and cookies for the holidays, and some kale back in August, and I feel entitled to this little popularity faux pas.)

I come from lands where every part of animal is used, cherished and cooked with a lot of love. In our love for offal we are not alone; nose-to-tail cooking is an integral part of the culinary life in countless countries around the world, where it is understood that no animal part should go to waste. They don't say, "you can eat all of the pig except the squeal", for nothing. Every time we eat meat an animal dies; to honor this sacrifice it is our duty to use the gift the animal gave us responsibly and prepare it with utmost respect. I gave up on preaching this idea to non-offal eaters a long time ago, having come to the realization that dislike for offal is one of the food-phobias that can be overcome only in the rarest of circumstances. Deeply rooted in cultural, anthropological, regional or religious customs, the uneasy feeling about offal is a part of the fundamental biological wiring of our personas and this is a battle that cannot be won. (However, I find incredibly amusing that foie gras is offal yet 90% of stylish offal-hating-foie-gras-gulpers do not seem to be aware of the fact.)

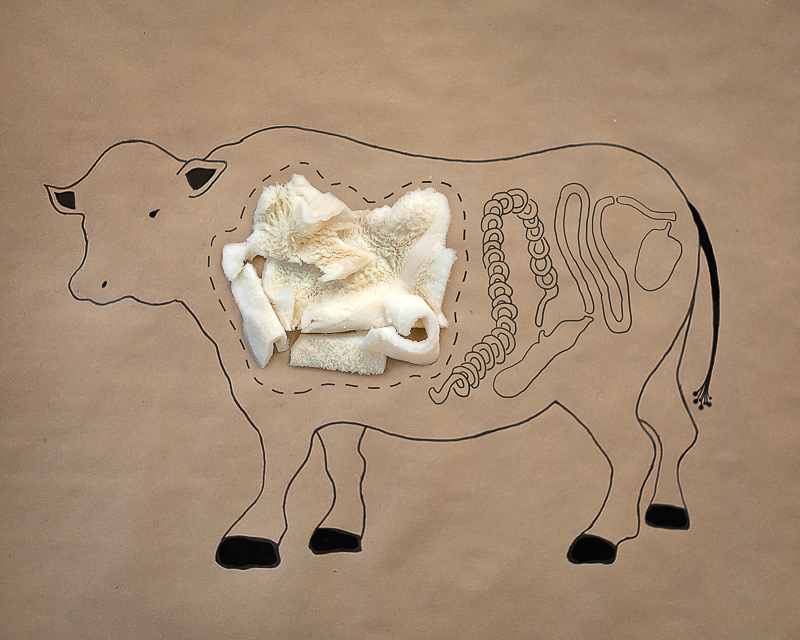

Back to my current meal. Tripe is a type of edible offal from the stomach of various farm animals, most notably beef. Beef tripe is usually made from one of the three, out of four cow's stomachs. Did you know that cow had four stomachs? As a matter if fact, I did not. Somehow, I had lived under the impression that there are three stomachs in a cow, until Miss Pain, my six-year old daughter corrected me. I wonder where they learn all these things.

For centuries, tripe dishes have been cooked in kitchens around the world. Although it is the Italians, with their Trippa alla Romana and Trippa alla Fiorentina, and French, with their Tripes ŕ la Mode de Caen, who get most of the mentions, tripe are also prepared in Indonesia, Morocco, China, Bosnia, Spain, Peru, India (goat tripe), Catalonia, Romania, Sri Lanka, Portugal, Czech Republic, Libya, Ethiopia, Croatia, Poland, Ecuador, Chile, Zimbabwe, Scotland, Turkey, Philippines, Armenia, Mexico, South Africa, Kenya, Japan, Hungary, Vietnam, Germany, Botswana, Bulgaria, Iran, Macedonia, Jamaica, Slovenia, Pakistan, Nigeria, Jordan and Serbia...

Believe it or not, Serbia happens to be the home to one of the oldest recorded dishes with tripe, dating back to the 13th century. Here we go, didn't I tell you that I come from the lands of offal. Known as Шкембиђи у Сафту (from shikambeh the Persian word for 'stomach'), translated Tripe in Sauce, is the version of the ancient dish still very much alive and very much loved. Шкембиђи у Сафту is not rocket science; it is a simple stew of tripe simmered in a sauce of onions, garlic, carrot and tomato. Unlike many other regional dishes that can vary vastly depending on a family, part of the country, and sometimes even cook's mood, the recipe for Шкембиђи is almost carved in stone, remaining pretty consistent to the ancient ways rooted in the peasantly impoverished nature of the region. One probably does not have to be a master chef to make decent Tripe in Sauce, but making pretty-darn-good Tripe in Sauce requires a tiny bit of knowledge about cow's anatomy. The fact that cow has four stomachs is not only an interesting trivia, but fundamental to the success of any ambitious Tripe in Sauce project. The four stomachs produce four kinds of tripe. The rumen, or the first stomach, produces flat looking tripe known as "blanket" or "pile". A layer of fat, which must be removed, often accompanies pile tripe. From the reticulum, the second stomach, comes the "honeycomb" tripe, a piece of stomach with a beautiful hexagonal tiling that looks, well, just like its name suggests, the honeycomb. This type of tripe is deemed the most desirable; it is the most tender and meatiest stomach, which keeps its shape during cooking and traps the sauce within its richly textured surface. The third stomach, the omasum, is the home to "leaf" or "book" tripe, a type of tripe commonly offered in Chinese restaurants. When you kill a cow, at least in the olden days, there was no pick and choose, and the ancient tripe was prepared from a combination of all three. And that my friends, is the secret to the very best Tripe in Sauce, the secret to achieving a layer after layer of different textures, a perfect combination of three different levels of gooeyness, and a multi-dimensional stringy quality that becomes more pronounced with each bite. (The ancient Serbs were not alone in this discovery, and many other serious recipes are quite strict about the need for a combination of different kinds of tripe.)

I do not particularly cherish exercises in cow's anatomy, but for the purpose of this project we will also have to pay attention to the fact that tripe is predominantly made of connective tissue and water. Connective tissue is tenderized the best via slow cooking, and although nowadays tripe is almost always sold cleaned and parboiled, tripe will still require a long slow cook - so parboiled or not you are looking at about three or more hours of simmering to achieve the level of tenderness needed for a mouthwatering tripe dish. Water in tripe is irrelevant to the taste or texture of the final product, but is important in the economics of the dish, because the cooking process will reduce the amount of tripe by half, so bear in mind when making the shopping list.

Other than that, I should probably mention that while being cooked, tripe tends to exhibit, well how shall I put it, not a remarkably pleasant smell. The smell is typically associated with raw, untreated tripe, known as green tripe. Today, when you buy your tripe from the market it has already been cleaned, parboiled and frequently bleached to remove the color and odor. No matter how clean your purchase might be, chances are that it can still be improved with a little extra rinse, a couple of quick baths, followed by a nice long soak in water/vinegar mixture. (This will also take care of not terribly unpleasant, but particularly undesirable bleachy smell that accompanies bleached tripe.)

That about covers the key facts. As I read back, I realize that this is a loooooong post, and most likely by now only very few readers remained. And who can blame the departed ones - offal and biology of a cow are not exactly the best-seller topics. But the ones who endured are up for a reward, because what follows is the very recipe for the Ancient Tripe.

Tripe in Sauce (Шкембиђи у Сафту)

- 2 to 2 1/2 lb tripe (preferably honeycomb, leaf and blanket combined)

For the bath

- 1/3 cup cider vinegar

For cooking the tripe

- 2 carrots, coarsely chopped

- 2 stalks of celery, coarsely chopped

- 1 yellow onion, quartered

- 2 bay leaves

- 8 black peppercorns

For the stew

- 2 medium yellow onions (about 8 oz), finely minced

- 2 medium carrots (about 8 oz), finely shredded

- 2 cups tomato sauce or crushed tomatoes

- 6-7 cloves of garlic, minced

- 2 tbsp sunflower oil

- 2 bay leaves

- 2 tsp flour

- 2 tsp sweet Hungarian paprika

- Salt and freshly ground pepper

- Some fresh parsley to garnish

Wash the tripe carefully. Fill a large pot with water, add the cider vinegar and soak the tripe for about four hours. Remove the tripe from the soak and discard the water. Rinse the tripe again to remove any traces of vinegar. In a large pot combine the tripe, chopped carrots, celery, onion quarters, bay leaves and peppercorns. Add enough water to cover the tripe by two to three inches. Cover, bring to a boil, reduce to simmer and simmer for about three hours. Tripe is done when it is very soft and tender, but not mushy. Remove the tripe from the broth and allow them to cool. Discard the cooking broth or keep for a different use. Cut the tripe in 1/2 to 3/4 inch thick strips. In a medium casserole heat the oil. Add the minced onion and sauté for a couple of minutes, until onion is golden and soft. Add the carrots and continue to sauté for another couple of minutes. Add the garlic and tripe, sprinkle with flour and Hungarian paprika and mix well. Add in the tomato sauce, about 2-3 cups of water, bay leaves, season with salt and pepper and simmer for about 40 minutes. (If needed add more water throughout cooking. The final dish should be of a stew-like consistency, with tripe completely covered with sauce but not swimming in it.) Remove casserole from the heat, if needed adjust the seasoning, garnish with fresh parsley, and serve with boiled potatoes or fresh bread. Serves four.

P.S. - My mom likes to make a variation of this dish, where after about twenty minutes of cooking, the stew is transferred into the oven and then baked at 350 °F, until it forms wonderfully crunchy top layer. I cannot decide which version I like better (the photos of both dishes attached) and will leave it up to you to decide. Should you ever embark on this adventure.

- L'articolo "The Magnificent Offal: Шкембиђи у Сафту a.k.a. The Ancient Tripe" a firma di Queen Sashy è apparso sul blog Three little halves che ringraziamo per averne autorizzato la ripubblicazione.